Nature or nurture? Thousands of crabs migrate each spring in Cuba, crossing major roads in their journey.

Where does poetry start? What defines a poem, or transforms prose into something poetic? Just as we ask what creates a person – their birth or their upbringing – so I am beginning to think it is with poetry.

I consider myself to be a master of Free Verse. Is this lazy, I wonder? Does it mean I am not, truly, a poet? Surely I should be able to manipulate words such that my poetry gains strength from syllables? From rhyme? I certainly appreciate and enjoy formal poetry and am often in awe of well-rhymed poems.

Yet I do utilise form, structure and rhyme in all my poems. And sometimes I think that the words free verse are something of a misnomer – a dumbing down or devaluing of poetry based purely on the fact that structure may not be immediately apparent. So a poem lacks a rhyming pattern. The stanzas (if any) are not uniform. Does this make the poem any less potent? Any less strived over? Less worthy?

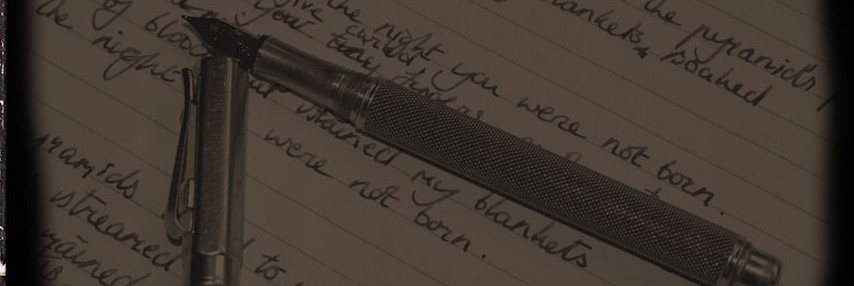

All my poems are fuelled by passion, form, rhyme (more likely internal for me). I use assonance, alliteration. I spend ages considering my words. I play with line breaks. I read, rewrite, re-read. I consider the power of a word when placed at the end of a line, the beginning of a stanza, on its own line. Every break in rhythm, every syllable is carefully constructed and deconstructed and reconstructed until I think I’ve explored every possibility and created a piece of writing that is both musical and meaningful.

This week I wrote Bachcha (it means child in Hindi). I wanted to write about this difficult subject, I wanted to create rich images that juxtaposed the beautiful with the horrific and yet I began the poem lost for words – as my first stanza tells you.

And I noticed that I had still used assonance and imagery even when I felt I was pulling hens’ teeth (to break a writer’s golden rule and use a cliché). So how much of poetry is innate?

I reckon it is this internalised poetry (nature) that first allows us to put pen to paper but it is nurture that necessitates repeated editing and rewriting. It is nature that ensures our poetic voice shines through but nurture makes our finished work appear accomplished.

Nature means you cannot steal my work (it wouldn’t sound like you). Nurture means you should recognise the time I’ve spent – and appreciate the final product.

I didn’t think I could write Bachcha, I felt I hadn’t the words but the part of me that simply writes gave me the bare materials to complete a poem that others describe as powerful.

What do you think?